__________________________________________

I would like to write this article a bit differently than I usually write articles. I would like to share with you a bit of the thinking process that I went through as I investigated the issue of Hag HaShavuoth (the Festival of Weeks) in the Torah. One of the basic tenets of Karaism is that every Israelite has the ability, and consequently, the responsibility, to examine issues in the Torah for himself. This is encapsulated in the well-known Karaite proverb, "Search well in the scriptures and do not rely on my opinion."1 In opposition to the doctrine commonly taught today in Rabbinical yeshivas (study halls) known as "The Decline of the Generations" — which says that each successive generation of Israelites is farther away from the revelation at Mount Sinai and therefore less capable of understanding the Torah — I believe that our generation has the greatest potential to comprehend the Torah since First Temple times.

It is a fact that our generation is one of the first in thousands of years to be blessed by Yehowah to return to our ancient homeland, to recreate our ancient culture, and to speak our ancient language. Yehowah has turned the cup of staggering into one of sweet wine2 and has desired to bless us and turn his face towards us. The fact that we, as a nation, have largely squandered this incredible blessing, is tragic. Nonetheless, I believe that the blessing is still there for those individuals who wish to take advantage of it.

Therefore, not only is it possible for us to better understand the Torah than even the famous teachers of the exile (Rabbanite and Karaite alike), but it is our solemn responsibility to do so, lest we squander the blessing given to us by Yehowah and spit in the face of the Elohim of Israel.

__________________________________________

The issue of when the Children of Israel are to celebrate Hag HaShavuoth is not a recent one. Indeed, a dispute had already surfaced between the Sadducees and the Pharisees during the Second Temple period. The Babylonian Talmud reports:

"[The reaper would then ask], 'Shall I reap?' and they would say, 'Reap!' [He would then repeat,] 'Shall I reap?' and they would say, 'Reap!' [He would state the question] three times in every case, and they would say, 'Yes, Yes, Yes.' Why was all of this necessary? Because of the Boethusians, who said that the reaping of [barley for] the Omer [HeTenufah offering] should be done not upon the departure of the Holiday [of the First Day of Hag HaMazoth, but on the first Saturday night after that Holiday.]"3

Surely, as a Karaite, it would be very tempting to assume a priori that the Karaite point of view is correct and that the Rabbanite point of view is incorrect. However, I have decided that, in order to be a true Karaite, I must not automatically accept the Karaite view. Rather, I must "search well in the scriptures, and not rely upon anyone’s opinion."

It is with this frame of mind that I begin my investigation into the holiday of Shavuoth, and I invite you to join me. Should the evidence be in accordance with the traditional Karaite view, I am ready to accept this. On the other hand, should the evidence favor the Rabbinical point of view, I am prepared to admit truth where I see it. Finally, should the evidence point to a conclusion which is neither Karaite nor Rabbanite, I am prepared to accept that as well.

I won’t present my findings yet. Rather, I will lead you through the thought process, so that you may draw your own conclusions. This will allow you to better perceive whether what I am saying is fair and honest. Let us begin our journey in Leviticus 23, the place in the Torah where all of the Biblical holidays are described.

__________________________________________

"[9] And Yewowah spoke to Moshe saying, [10] Speak to the Children of Israel and say to them, When you come into the land which I give to you, and you harvest its harvest, you shall bring a sheaf of the first of your harvest to the Cohen. [11] And he shall wave the sheaf before Yehowah so that He may be pleased with you. On the day after the shabbath the Cohen shall wave it. [12] And on the day you wave the sheaf, you shall prepare a year-old unblemished lamb as a burnt offering to Yehowah [13] and its gift offering, two-tenth parts of fine flour mixed with oil — a fire offering to Yehowah, a sweet scent — and its drink offering, a fourth of a hin of wine. [14] And you shall not eat bread, roasted grains and ripe grains until this very day, until you bring the offering of your Elohim. This is an eternal statute throughout your generations in all your dwelling places." [15] And you shall count for yourselves, from the day after the shabbath, from the day of your bringing the sheaf to be waved, a total of seven shabbaths, [16] until the day after the seventh shabbath; you shall count fifty days, and then you shall bring a new gift offering to Yehowah. [17] From your settlements you shall bring bread as a wave offering; it shall be two loaves from two tenths [of an ephah] of fine flour; it shall be baked leavened as first fruits to Yehowah. [18] And you shall offer with the bread seven unblemished year-old lambs, one young bull and two rams. They shall be a burnt offering to Yehowah, together with their gift offering and their drink offering — a fire offering, a sweet smelling scent to Yehowah. [19] And you shall prepare one male goat as a sin offering and two year-old lambs as a peace offering. [20] And the Cohen shall wave them together with the first-fruits bread as a wave offering before Yehowah, together with the two lambs. They shall be holy to Yehowah for the Cohen. [21] And on this very day you shall proclaim that it shall be a holy convocation for you. You shall not do any unnecessary work. This is an eternal statute in all your settlements throughout your generations."4

First, let's review a couple of facts about the above verses:

(1) Verse 11 states that the Omer HaTenufah (Wave Sheaf) offering is to be brought on the day after the shabbath.

(2) Verse 15 states that from the day the sheaf is waved, which is the day after the shabbath, a total of seven shabbaths is to be counted.

(3) Verse 16 states that a new meal offering is to be brought on the day following the seventh shabbath. This day is Hag HaShavuoth (The Festival of Weeks).

The central question here is, What is meant by the word "shabbath" in these verses? This question has always constituted the crux of the disagreement between the Sadducees and Pharisees, and later, between the Karaites and the Rabbanites. We first take a look at the Rabbinical point of view and, following this, the Karaite point of view.

__________________________________________

The Rabbanites claim that the four instances of the word "shabbath" in the above verses mean, respectively, "the first day of Hag HaMazoth", "the first day of Hag HaMazoth", "weeks", and "week". Thus, the relevant verses are rendered by the Rabbis as follows:

Verse 11: "And he shall wave the sheaf before Yehowah so that He may be pleased with you. On the day after the first day of Hag HaMazoth, the Cohen shall wave it."

Verse 15: "And you shall count for yourselves, from the day after the first day of Hag HaMazoth, from the day of your bringing the sheaf to be waved, a total of seven weeks."

Verse 16: "Until the day after the seventh week, you shall count fifty days, and then you shall bring a new gift offering to Yehowah."

Thus, according to the Rabbanites, the Omer HaTenufah (Wave Sheaf) offering is always brought on the day following the first day of Hag HaMazoth (The Festival of Unleavened Bread). Since the first day of Hag HaMazoth falls on the 15th of the First Month5 (which the Rabbanites call "Nissan"), the Omer HaTenufah offering is always brought on the 16th of the First Month.

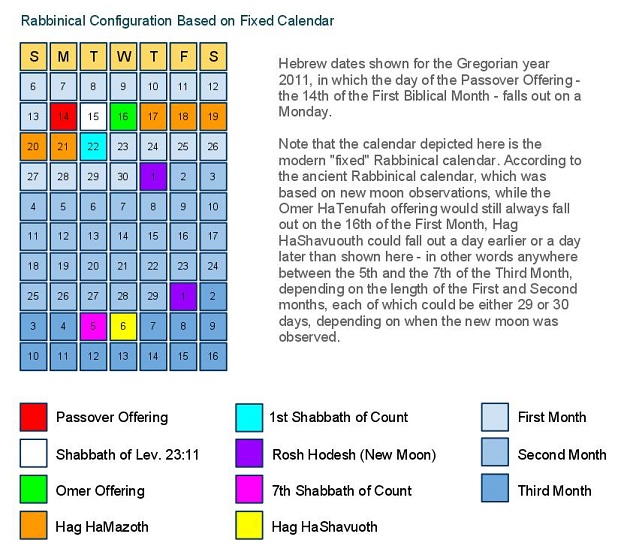

Therefore, starting on the 16th of the First Month, seven weeks (periods of seven days) are counted by the Rabbanites. The day following the 7th day of the 7th week (i.e. the day following the 49th day of the count) is Hag HaShavuoth which, under the Rabbinical calendar currently in use, always falls out on the 6th day of the Third Month (which the Rabbanites call "Sivan".)

__________________________________________

By contrast, the Karaites interpret the word "shabbath", in all cases, to be the Shabbath, i.e. the seventh day of the week, on which we rest. According to the traditional Karaite interpretation, the shabbath referred to in verse 11 and again in verse 15 (first occurrence) is the first Shabbath ("Saturday") that occurs, starting on the day on which the Passover sacrifice is brought, i.e. the 14th of the First Month.6

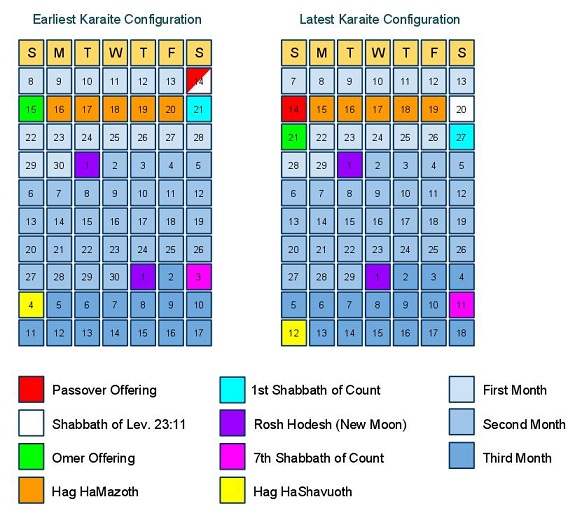

Since the Shabbath occurs every seven days, this special Shabbath falls somewhere between the 14th and the 20th of the First Month, inclusive. Therefore, the "day after the shabbath" referred to in verses 11 and 15 is the first (and only) "Sunday" which falls between the 15th and the 21st of the First Month, inclusive — precisely the same seven days of Hag HaMazoth. In other words, the traditional Karaite view is that the Omer HaTenufah offering is brought on the "Sunday" during Hag HaMazoth.

It is on this "Sunday" that the 49 day count towards Hag HaShavuoth begins. Since the count begins on a "Sunday", the seven shabbaths mentioned in verse 15 (second occurrence) are actual Shabbaths (i.e. "Saturdays"), which fall out on the last day of each of the seven weeks of the count: the 7th day of the count is the first Shabbath after the "special" Shabbath, the 14th day is the second Shabbath after, etc., until the seventh Shabbath is reached, which is equivalent to the 49th day of the count. Finally, Hag HaShavuoth occurs on the following (50th) day and, like the Omer HaTenufah offering which marks the beginning of the count, falls on the First Day of the week, i.e. "Sunday".

Hag HaShavuoth always falls in the Third Biblical Month, but the actual date of the month on which it falls is not set in advance. Rather, it varies, depending on the date on which the 50-day Omer HaTenufah count commences, as well as the dates on which the new moons of the Second and Third months are sighted, as the Omer HaTenufah count crosses both of these new moon boundaries.

The earliest possible date for Hag Shavuoth is the 4th day of the Third Month. This will occur if the Omer HaTenufah count begins on its earliest date possible — the 15th of the First Month — and if the new moons of both the Second and Third months are observed on the 30th days following their previous new moons, i.e. if both months are long rather than short.

The latest possible date for Hag Shavuoth is the 12th day of the Third Month. This will occur if the Omer HaTenufah count begins on its latest date possible — the 21st of the First Month — and if the new moons of both the Second and Third months are observed on the 29th days following their previous new moons, i.e. if both months are short.

To sum up what we have learned so far, the Karaite interpretation of the relevant verses is as follows:

Verse 11: "And he shall wave the sheaf before Yehowah so that He may be pleased with you. On the day after the Shabbath ('Saturday') [that falls between 14th and the 20th of the First Month] the Cohen shall wave it."

Verse 15: "And you shall count for yourselves, from the day after [this] Shabbath, from the day of your bringing the sheaf to be waved, a total of seven Shabbaths ('Saturdays')."

Verse 16: "Until the day after the seventh Shabbath ('Saturday'), you shall count fifty days, and then you shall bring a new gift offering to Yehowah."

Now that we have established the facts about both the Rabbinical and Karaite understandings of the Omer HaTenufah offering and Hag HaShavuoth, let us begin to examine the evidence for each of the two respective views. We begin with the Karaite view, and the Rabbinical view will become quite clear as a response to it.

__________________________________________

In contrast to all other holidays mentioned in the Torah, Hag HaShavuoth is the only holiday which is not given a specific date.

If we look through the entire Torah, we see that all of the Biblical holidays, with the singular exception of Hag HaShavuoth, are given specific dates:

The Pesah (Passover) Offering and Hag HaMazoth [Leviticus 23:5-6]: "[5] In the First Month, on the 14th day of the month, at dusk, is Yehowah's Passover. [6] And on the 15th day of the same month is the Feast of Unleavened Bread to Yehowah. Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread."

Yom HaTeruah (Rabbinical "Rosh HaShana") [Leviticus 23:24]: "[24] Speak to the children of Israel, saying, In the Seventh Month, on the 1st day of the month, shall be a day of rest for you, a remembrance achieved by making noise [to the heavens], a holy convocation."

Yom HaKippurim [Leviticus 23:27]: "[27] Also, on the 10th day of this Seventh Month is the Day of Atonement; there shall be a holy convocation for you, and you shall afflict yoursleves, and you shall bring a fire offering to Yehowah."

Hag HaSukkoth and "Shmini Azereth" [Leviticus 23:34-36]: "[34] Speak to the children of Israel, saying, On the 15th day of this Seventh Month is the Feast of Tabernacles, for seven days, to Yehowah."

While Hag HaShavuoth is the only holiday in the entire Torah that never has a specific date associated with it, according to the Rabbinical understanding, Shavuoth (in modern times) always falls out on a specific date, the 6th day of the Third Month (which the Rabbanites call "Sivan") — exactly 50 days after the 16th day of the First Month ("Nissan"), the day on which, according to the Rabbinical interpretation, the Omer HaTenufah offering is brought.

The fact that a specific date is not mentioned for Hag HaShavuoth strongly supports the Karaite contention that Hag HaShavuoth does not fall out on a specific date at all but, rather, varies depending on the date of the bringing of the Omer HaTenufah offering, which, as explained earlier, can be anywhere between the 15th and the 21st of the First Month, according to the traditional Karaite view.

It must be pointed out that, before the early centuries of the Common Era (which is commonly abbreviated as "CE"), at which time the Rabbis adopted the fixed Hebrew calendar, even if the Omer HaTenufah offering were fixed on the 16th of the First Month as the Rabbis claim, still, the date on which Hag HaShavuoth fell would have been variable. This is because the Omer HaTenufah count of 50 days crosses two new moon boundaries: that of the Second Month ("Iyar") and that of the Third Month ("Sivan"). Depending on when these two new moons were sighted, the First and Second Months ("Nissan" and "Iyar") could have contained either 29 or 30 days:

If both the First Month and the Second Month were short — meaning that only 29 days passed from their inceptions until the following new moon — then Shavuoth would have fallen out on the 7th of Sivan. If both months were long — containing 30 days — then Shavuoth would have fallen out on the 5th of Sivan. And if one was short and one long, then Shavuoth would have fallen out on the 6th of Sivan, as it does today according to the fixed Rabbinical calendar.7

In modern times, this becomes irrelevant since the Rabbanites now use a fixed calendar in which the First Month ("Nissan") always has 30 days and the Second Month ("Iyar") always has 29 days. In this fixed calendar, Shavuoth will indeed always fall out on the 6th of Sivan.

Perhaps, then, a better question to ask the Rabbanites is, "Why does the Torah not mention a specific date for the Omer HaTenufah offering, since according to the Rabbanites, it must always fall out on the 16th of Nissan, whether a fixed calendar or an observation-based calendar is in use?" For this question, the Rabbis have no compelling answer.

The omission of a specific date for Hag HaShavuoth supports the Karaite contention that the date of Hag HaShavuoth is not fixed. However, it is not conclusive in and of itself. It is possible that the date is omitted because, even according to the Rabbinical understanding of the holiday, the date of Hag HaShavuoth would have been variable, before the adoption of their fixed calendar. However, this does not explain why the Omer HaTenufah offering is not given a specific date in the Torah.

The word "shabbath" is a specific word in the Torah which always refers to precisely one of three things: The Shabbath (the seventh day of the week), Yom HaKippurim, and the Seventh Agricultural Year (known in modern Hebrew as the "Shmita" year). Therefore, it is not plausible that the word "shabbath" could refer to the first day of Hag HaMazoth, as the Rabbis claim it does in verses 11 and 15 (first occurrence).

The Rabbanites claim that the word "shabbath" in Leviticus 23:11 and 23:15 (first occurrence) refers to the first day of Hag HaMazoth, because the similar word "shabbathon" refers to a number of the Torah's holidays, as can be seen in the following verses:

Yom HaTeruah [Leviticus 23:24]: "[24] Speak to the children of Israel, saying, In the Seventh Month, on the 1st day of the month, shall be a ceasing from work (shabbathon) for you, a remembrance achieved through shouting, a holy convocation."

Hag HaSukkoth and "Shmini Azereth" [Leviticus 23:39]: "[39] Also, on the 15th day of the Seventh Month, when you gather the produce of the land, you shall celebrate a festival to Yehowah for seven days. On the first day shall be a ceasing from work (shabbathon) and on the eighth day shall be a ceasing from work (shabbathon).

Since the above two holidays can be referred to as a "shabbathon", claim the Rabbis, it is reasonable to assume that the first day of Hag HaMazoth can also be referred to as a "shabbathon" and, taking this one step further, that it can be referred to as a "shabbath", even though neither of these two words is ever used explicitly in the Torah to describe the first day of Hag HaMazoth.

A linguistic and contextual analysis of the words "shabbathon" and "shabbath" in the Tanach bear out that while the first part of the above claim may be true, the second part is clearly not. The word "shabbathon" is, indeed, a general term meaning "a ceasing from work", and therefore appropriately describes many of the Torah's holidays, including the first day of Hag HaMazoth.

However, the word "shabbath" — although related in linguistic root — is an all-together different concept. The word "shabbath" is a proper noun, the name of precisely three events in the Torah: the Shabbath (seventh day of the week), Yom HaKippurim and the Seventh Agricultural ("Shmita") Year:8

Shabbath [Exodus 20:8-10]: "[8] Remember the Shabbath day to keep it holy. [9] Six days you shall work, and do all your necessary tasks, [10] but the seventh day is the Shabbath to Yehowah your Elohim. You shall not do any work, not you, nor your son, nor your daughter, nor your male servant, nor your female servant, nor your domesticated animals, nor your sojourner that is within your gates."

Yom HaKippurim [Leviticus 16:29-31]: "[29] It shall be an eternal statute for you, in the Seventh Month on the 10th of the month, you shall afflict yourselves and you shall not do any work, neither the native born nor the sojourner who lives among you. [30] For on this day, you shall atone for yourselves, to purify yourselves from all your sins before Yehowah, so that you may be pure. [31] It is a Shabbath, a ceasing from work ('shabbathon') for you, and you shall afflict yourselves. This is an eternal statute."

The "Shmita" Year [Leviticus 25:1-5]: "And Yehowah spoke to Moshe on Mount Sinai saying, [2] Speak to the children of Israel and say to them, When you come into the land which I have given you, the land shall rest a Shabbath to Yehowah. [3] Six years shall you plant your fields, and six years shall you prune your vineyards, and gather in [the land's] produce. [4] But the seventh year there shall be a Shabbath, a period of rest ('shabbathon') for the land, a Shabbath to Yehowah. You shall not plant your fields, and you shall not prune your vineyards. [5] That which grows by itself of your harvest you shall not reap, and the grapes of your abandoned vines you shall not gather. It shall be a year of rest ('shabbathon') for the land."

So why are Yom HaKippurim and the Seventh Agricultural Year each referred to as a "Shabbath"? The answer is that, in reality, the "true" Shabbath is the Seventh Day of the Week, while Yom HaKippurim and the Seventh Agricultural Year are "Shabbaths" by extension, because they share certain important properties with the "true" Shabbath. In the case of Yom HaKippurim, it is the complete cessation from melakha (work) which is shared; in the case of the "Shmita" year, it is the fact that it occurs every seven years (analogous to the Day of Rest occurring every seven days), and that a complete cessation from all planting is called for.

Aside from these three distinct events, nothing else in the entire Tanach is ever called a "Shabbath". However, each of these three "Shabbaths" is also referred to as a "shabbathon" — in Exodus 31:15, Leviticus 23:32, and Leviticus 25:4, respectively.9 Thus, all "Shabbaths" are "shabbathons", but the converse is not true: not all "shabbathons" are "Shabbaths".

The table below summarizes the situation:

| Shabbath (and Shabbathon) | Shabbathon (but not Shabbath) |

|---|---|

| Seventh Day of the Week | Yom Teruah |

| Yom HaKippurim | First Day of Sukkoth |

| Seventh Agricultural Year | Eighth Day of Sukkoth |

Therefore, when analyzing to which of the above two groups the first day of Hag HaMazoth most naturally belongs, we can conclude that it is the second ("Shabbathon only") group, and not the first ("Shabbath and Shabbathon") group, since it is never mentioned explicitly as a "Shabbath", and since its level of cessation from melakha most resembles that of the second group.

The first point is explicit in the text of the Torah, while the second point is clear from an examination of Leviticus chapter 23, the list of the Torah's mo'adim (holidays). While, on both the Shabbath and Yom HaKippurim, the Torah prohibits the Children of Israel from doing "melakha" (Leviticus 23:3,28), on the holidays mentioned in the second ("Shabbathon only") group, the Torah prohibits them from doing "malekheth avoda". In the case of the first day of Hag HaMazoth, it is "malekheth avoda" that is prohibited (Leviticus 23:7), and not "melakha". The word "melakha", reserved in Leviticus 23 for the most solemn holidays, implies a stricter level of refraining from work, as evidenced by the explicit commandment not to light a fire on the Shabbath (Exodus 35:3), while the phrase "malekhet avoda" is reserved for the remaining holidays and implies a level of greater leniency, including the explicit allowance to prepare food on the first day of Hag HaMazoth (Exodus 12:16).10

From an examination of the word "shabbath" in the Torah, it is highly unlikely that the first day of Hag HaMazoth could ever be referred to as a "shabbath", as the Rabbis claim it is in Leviticus 23:11 and 23:15 (first occurrence). Since the word "shabbath" only refers to one of three events in the Torah — the Shabbath, Yom HaKippurim and the Seventh Agricultural Year — this strongly supports the Karaite view that the shabbath mentioned in these verses is an actual Shabbath, i.e. the seventh day of the week, and not the first day of Hag HaMazoth.

The Karaite explanation of the four occurrences of the word "shabbath" as always meaning "The Shabbath", i.e. the seventh day of the week, is simpler and requires fewer assumptions than the Rabbinical explanation as meaning, alternatively, "the first day of Hag HaMazoth" and "week".

It might be helpful at this point to review the concept of "Occam's Razor", a basic principle of rhetoric and argumentation. Occam's Razor states that, given competing explanations for the same phenomenon, the simplest one, (which is defined as the one which makes the fewest assumptions), should be considered to be the correct one.

Let's consider an example. You are walking down the street and you see a fire engine suddenly speed by with its lights flashing. Occam's Razor posits that it would be correct for you to assume that the fire engine is on its way to respond to an emergency, and not that the gas pedal is stuck and that the driver has turned on the lights because he is afraid of the dark. The first explanation is the "simplest" one — it makes the fewest assumptions — while the second explanation is unnecessarily complex. Given the lack of any further evidence to support the second explanation, the first explanation should be assumed to be the correct one, even though, statistically, there still is some small chance that the second explanation is correct.11

Now let's apply the principle of Occam's Razor to the competing Karaite and Rabbanite explanations of the verses in question. Since the Karaite interpretation of these verses renders all four occurrences of the word "shabbath" as "The Shabbath", i.e. the "Seventh Day of the Week", all four occurrences are (a) identical to each other, and (b) consistent with the basic meaning of the word "shabbath", as discussed in the previous section.

By contrast, the Rabbanite explanation fails on both these counts. The Rabbinical interpretations of "shabbath" in the relevant verses are (a) not identical to each other, since the word can mean either "the first day of Hag HaMazoth" or "week", and (b) not consistent with one of the three basic meanings of the word "shabbath" as "The Shabbath", "Yom HaKippurim" or the "Seventh Agricultural Year".

Let us delve further.

We have previously considered, and largely rejected, the Rabbinical claim that the word "shabbath" can mean "the first day of Hag HaMazoth". Now, let us consider the Rabbinical claim that the word "shabbath" means "week", as the Rabbis claim it does in its second appearance in verse 15 (where it appears in the plural form "shabbathoth"), and in verse 16.

An examination of every single occurrence of the word "shabbath" in the entire Tanakh reveals that nowhere else is the word "shabbath" ever used to mean "week". The terms used in the Torah to describe a period of seven days (or years) are either "shavua" (in Genesis 29:27-28, Leviticus 12:5 and Yehezqel 45:21, for example) and, more frequently, "shivath yamim" (in Exodus 7:25, 22:29 and Numbers 19:16, for example.)

However, before completely rejecting the Rabbinical understanding of shabbath as "week", we must examine some evidence in favor of such an interpretation. Ironically, the Rabbis themselves never raise the following point.12

The evidence we must consider is the parallelism between the word "shabbathoth" (shabbaths) in Leviticus 23:15 and the word "shavuoth" (weeks) in Deuteronomy 16:9, two separate instances of the counting from the Omer HaTenufah:

Leviticus 23:15: "And you shall count for yourselves, from the day after the shabbath, from the day of your bringing the sheaf to be waved, a total of seven shabbathoth (shabbaths).

Deuteronomy 16:9: "You shall count for yourself seven shavuoth (weeks). From the time the sickle is first upon the upright grain stalks, you shall begin to count seven shavuoth (weeks)."

By comparing these two verses, we see that the word shabbathoth (shabbaths) in Leviticus 23:15 is in parallel with the word shavuoth (weeks) in Deuteronomy 16:9. Often in the Tanach, parallelism implies synonymy. That is to say, distinct words which appear in the same context across two or more verses can have similar meanings. Synonymy through parallelism occurs frequently throughout the Tanach, since the Tanach often repeats laws or retells events two or more times, using slightly different language in each telling. Indeed, Karaite scholars have used the phenomenon of parallelism in the Tanach to assist them in understanding the meanings of words and phrases whose definitions have been lost or become unclear.

For example, one Karaite understanding of the mysterious word totaphoth (Exodus 13:16, Deuteronomy 6:8 and Deuteronomy 11:18) — generally translated by the Rabbis as "frontlets" — is that it simply means "a remembrance", because in Exodus 13:9, the word is replaced with zikaron, a remembrance:

Exodus 13:16: "And it shall be as a sign on your hand and as totafoth13 between your eyes ..."

Exodus 13:9: "And it shall be for you as a sign on your hand and as a zikaron (remembrance) between your eyes ..."

On the other hand, parallelism does not always imply synonymy. Two different versions of the same law or event might serve other purposes. For instance, in the two different tellings of the Ten Commandments, we find:

Exodus 20:8: "Remember (Zachor) the Shabbath to sanctify it."

Deuteronomy 5:12: "Keep (Shamor) the Shabbath to sanctify it, …"

Here, it cannot possibly be claimed that זכור (zachor) and שמור (shamor) are synonymous, since the meanings of both words are well established, as "remember" and "keep", respectively. Rather, in Deuteronomy 5:12, Moshe Karaieinu14 is expanding and elaborating upon the original commandment found in the book of Exodus, as he often does in the book of Deuteronomy. So, in this case, parallelism serves the purpose of expansion rather than synonymy.

In fact, by comparing Leviticus 23:15 and Deuteronomy 16:9, we see that what is really going on is that the same concept is being expressed in two different ways, not that the two words are synonymous. Since, according to the Karaite understanding, the weeks in question begin on "Sunday" and end with the conclusion of the Shabbath, counting seven consecutive Shabbaths is identical to counting seven weeks. The simplicity of the Karaite understanding seems to allow all the pieces of the puzzle to fit together quite nicely.

By contrast, the complexity of the Rabbanite understanding creates almost absurd consequences. Let us consider, for example, one of the extreme consequences of the duality of the Rabbinical interpretation of the word "shabbath". In verse 15, the word "shabbath" appears twice: the first time it is rendered by the Rabbis as "the first day of Hag HaMazoth", and the second time (when it appears in the plural) it is rendered by the Rabbis as "weeks". This means that there are two distinct meanings of the same word within the same verse! This is an unprecedented happening in all of the Tanach.

In response to this traditional Karaite criticism of the Rabbis' interpretation of these verses, the Rabbinical commentator Ibn Ezra scours the Tanach and finds only a single verse which contains the same word twice, each one with an entirely different meaning:

Judges 10:4: "And he had thirty sons that rode on thirty donkey colts (ayarim), and they had thirty cities (ayarim), which are called Hawwoth-yair unto this day, which are in the land of Gilad."

In this verse, the word עירים (ayarim) appears twice. In its first appearance it means "donkey colts", and in its second appearance it means "cities". The problem, however, with using this verse as proof is that the appearance of ayarim twice is a play on words, and the verse also includes the word שלושים ("thirty") three times, two of them before each occurrence of the word ayarim. The word play probably extends also to the word יאיר (Yair) which sounds similar to the word עירים (ayarim).15

In Leviticus 23:15, however, the Torah is not using word play.

Why, then, would the Rabbis accept the less simple interpretation of these verses? The answer to this question sheds great light on the difference in approaches to understanding the Torah between the Karaites and the Rabbanites.

After examining some classical Rabbinical explanations, it becomes obvious that the Rabbis considered problematic the fact that the Torah does not explicitly specify which Shabbath ("Saturday") is meant in Leviticus 23:11 and 15 for the bringing of the Omer HaTenufah offering. Therefore, they discarded all together the idea that the Omer HaTenufah offering is to be brought on the Shabbath, and replaced it with the idea that it is to be brought on the first day of Hag HaMazoth. They did so because, despite their constant claims that the Karaites interpret the Torah literally, it is actually the Rabbis who tend to do so. When the possibility of doing so breaks down — in this case, because the literal interpretation leads to ambiguity — they come up with an alternative explanation to circumvent the problem all together, and chalk up this counter-intuitive explanation to their "oral law".

The Karaites, when dealing with the very same ambiguity, apply logic, and reason that since the bringing of the Omer HaTenufah offering is mentioned directly following the verses describing Hag HaMazoth, it is most likely that the Shabbath in question falls near that holiday. Therefore, as a matter of tradition, the Karaites have settled on the Shabbath that falls between the 14th and the 20th of the First Month, as explained earlier. Since the Torah is indeed vague on the issue, the Karaites have never claimed that this is, without a doubt, the correct interpretation; rather, they have claimed that, in the absence of prophets, Levites serving in the Holy Temple, the Urim V'Tumim and the other tools that allowed answers and clarifications to be arrived at in ancient Israel, this is a reasonable enough explanation that it will suffice until the day when the above institutions are reinstated.

In short, the Rabbis and their followers seem to have a problem living with uncertainty and ambiguity, and this is one of the motivations for the creation of their so-called "oral law". The "oral law" serves as an "Opiate of the Masses", to shield them from one of the harsh realities of our current situation: that we have sinned, been punished with exile from our land, and, therefore, have lost a clear understanding of many of the Torah's commandments. But the Rabbanites prefer not to acknowledge this sad reality — not to themselves and certainly not to the rest of the world. Instead, they prefer to continue under the illusion that "all is well", and that they do indeed understand the Torah without ambiguity because they have the "oral law".

As a Karaite, I refuse to engage in such delusions, and am acutely aware that, as part of the curse that has come upon our nation, many of the true meanings of the Torah's commandments have been lost. Ironically, by approaching the study of the Torah with humility, as encapsulated in the millennium-old Karaite motto, "Search well in the scriptures ...", and by waiting and praying for the return of Yehowah to our (currently very sick) world with this same sense of humility, we can recover some of these ancient meanings. Nonetheless, the process will not be complete until prophecy returns to the Nation of Israel and until Yehowah resumes taking an active role in the running of the world. Then, "Yehowah will be king over the entire world. On that day, He will be one and His name will be one." [Zachariyah 14:9]

The Karaite interpretation is far cleaner and far simpler than the Rabbinical explanation, as it provides a single, consistent meaning for the word "shabbath" in its four occurrences in Leviticus 23:11-16. The Rabbinical explanation, by contrast, is complicated because it provides two distinct meanings for "shabbath": "the first day of Hag HaMazoth" and "week". Further, there is no precedent anywhere in the Tanach to support the Rabbinical contention that the word shabbath could take on either one of these two meanings. While the parallelism between Levticus 23:15 and Deuteronomy 16:9 might be used to that “shabbath” could mean "week", use of parallelism in this case is at best inconclusive. Further, accepting the Rabbinical explanation leads to the absurd result that a single word has two different meanings within a single verse, a phenomenon unprecedented anywhere in the Tanach except for Judges 10:4, where it is used as a play on words.

There is clear evidence in the book of Joshua 5:11 that the Israelites brought the Omer HaTenufah offering on the 15th of the First Month, a direct contradiction to the Rabbis' claim that it may only be brought on the 16th of the First Month, but perfectly in line with the traditional Karaite view that it is brought on the first Sunday between (and including) the 15th and 21st of the First Month.

Chapters 4 and 5 of the Book of Joshua tell of the Israelites’ entrance into the Land of Israel after their wandering in the desert for forty years. According to Joshua 4:19, the Israelites entered the Land on the 10th of the First Month:

Joshua 4:19: “And the people came up out of the Jordan [River] on the 10th of the First Month, and they encamped in Gilgal, on the east border of Jericho.”

The following chapter states that the children of Israel began to eat of the produce of the Land on the 15th of the First Month that year:

Joshua 5:10-12: "[10] And the children of Israel encamped in Gilgal, and they made the Passover [sacrifice] on the 14th day of the month in the evening in the plains of Jericho. [11] And they ate from the Land, on the day after (ממחרת) the Passover [sacrifice], unleavened bread and parched grain, on that very day. [12] And the manna ceased on the day after [the Passover sacrifice] when they began eating from the Land. And there was no more manna for the children of Israel, as they ate of the produce of the Land of Canaan that year."

Thus, the day on which the Israelites began to eat from the produce of the Land was the day after the bringing of the Passover Sacrifice, or the 15th of the First Month. Now, we know from Leviticus 23:14 that the Israelites are strictly forbidden from eating the new produce of the Land until the Omer HaTenufah offering is brought:

Leviticus 23:14: "And you shall eat neither bread, nor parched grains, nor fresh grains, until this very day, until you have brought the offering of your Elohim. This is an eternal statute throughout your generations, in all your dwelling places."

Thus, we can conclude that the Omer HaTenufah offering was brought in that year no later than the 15th of the First Month, a direct contradiction to the Rabbinical claim that it is to be brought only on the 16th of the First Month.16

Now, if we were to say that the first year of the Israelites’ entrance into the Land of Israel was a special case, so that the regular laws of the Omer HaTenufah offering did not apply, there are two responses:

1. First, the Torah, in Leviticus 23:10, says explicitly that the laws of the Omer HaTenufah offering go into effect "when you come into the Land":

Leviticus 23:10: "... When you come into the land which I have given to you, and you harvest its (grain) harvest, then you shall bring a sheaf of the first portion of your harvest to the Cohen."

2. Secondly, we see in Joshua 4:10 and 5:11 that the Israelites did not eat of the produce of the Land until the 15th of the First Month, even though they were already in the land on the 10th. It is clear that, for some reason, they waited until the 15th before eating of the produce of the Land. The most logical explanation (remember Occam's Razor?) is that they were waiting for the bringing of the Omer HaTenufah offering. Interestingly, note that even the manna continued to fall (in the Land of Israel!) until the 15th of the month.

How do the Rabbis respond to this very strong claim in favor of the Karaite point of view? Let's examine the response of one of the better known medieval Rabbinical commentators, Ibn Ezra. This will allow us not only to understand how the Rabbis respond to this particular claim, but to gain insight into the Rabbinical style of interpretation as opposed to the Karaite style of interpretation, in general.

One argument that Ibn Ezra uses is the "Two Passovers Argument":

"… The great one responded that there are two Passovers, God’s Passover and Israel’s Passover. God’s Passover is on the 15th at night [when He passed over the Israelites' houses], and thus the 'morrow after the Passover' (ממחרת הפסח) in Joshua [5:11] is the 16th [i.e. in accordance with the Rabbinical date for the Omer HaTenufah offering.] But the meaning of the 'morrow after the Passover' which is written in the Torah [in Numbers 33:317], is the [15th, the] morning after the Passover sacrifice [i.e. the morning after 'Israel's Passover' which occurs on the 14th]. ... Indeed, the only reason that the holiday is even called Passover is that God 'passed over' the houses. [Therefore, 'God's Passover' is the 'true' Passover.] And the day following this [true Passover is] the morning of the 16th. Likewise it is written, 'all that day, and all the night, and all the following day.' [Numbers 11:32]"

What the Ibn Ezra is actually trying to say here — believe it or not — is that there is not one, but (count 'em!) two Passovers: "Israel’s Passover" and "God’s Passover". "Israel’s Passover" is the Passover sacrifice, which is brought at the end of the 14th of the First Month ("between the evenings") as the sun dips towards the horizon. At the moment that the sun sinks below the horizon, the 14th day ends and the 15th begins. Later that night, "God’s Passover" occurs, commemorating Elohim's 'passing over' the houses of the Israelites and killing the first born of Egypt. Therefore, says the Ibn Ezra, the "morrow after the Passover" (ממחרת הפסח) mentioned in Joshua 5:11 is not the 15th, which would be the morrow after "Israel’s Passover", but rather, it is the morrow after (the completion of) "God’s Passover", which is the 16th, and is therefore completely in line with the Rabbinical understanding of the date of the Omer HaTenufah offering.

This would be a great argument except for one minor problem: it is absolutely ridiculous, and not even worth a mention except to show to what absurd degrees the Rabbinical commentators will go in order to justify their Rabbinical party line. Unfortunately, Orthodox Rabbinical Jews are so blindly convinced that their way of understanding the Torah is correct — and that their "Oral Law" has canonical, if not divine, status — that even when their interpretations fly squarely in the face of objective evidence, they will bend the very institutions of logic and reasoning just to maintain the illusion of their correctness.

But there is no getting around it: Ibn Ezra's argument is in clear contradiction with the simple language of the Tanach. Let us examine a number of Karaite rejoinders to the "Two Passovers" argument:

1. The first and most important point to make is that the context of Joshua 5:11 clearly shows that the Passover referred to is the Passover sacrifice: verse 10 speaks explicitly about the bringing of the Passover sacrifice, and verse 11 continues this thought. To assume that verse 11 suddenly switches over to (some unheard-of-before concept known as) "God's Passover" is counter-intuitive, which is exactly what Ibn Ezra's explanation is.

2. Next, throughout the entire Tanach, whenever the word פסח ("pesah") appears as a noun, it is always referring to the Passover offering and it is never referring to anything else, not "God's Passover", and not even the holiday which today we incorrectly call "Passover", but in reality is called the "Festival of Unleavened Bread" (חג המצות) in the Tanach. Thus, the morrow after the Passover can only mean the morrow after the Passover sacrifice, i.e. the morning of the 15th, and cannot possibly mean the 16th as Ibn Ezra claims it does.

3. Finally, even if we were to assume for a moment that the Passover referred to in Joshua 5:11 is "God’s Passover" and takes place in the middle of the night of the 15th, then the morning following "God's Passover" (ממחרת הפסח) would still be the morning of the 15th and not the morning of the 16th. This is because morning always follows evening in the Torah's reckoning of days. Because of this, Ibn Ezra must further complicate his explanation and say that the morning following "God's Passover" is actually the morning following the conclusion of "God's Passover".

Applying this logic to other verses in the Tanach brings us to absurd results. For instance:

Lot's firstborn daughter lies with him [Genesis 19:33-34]: "[33] And they gave their father wine to drink that night (לילה). And the first born [daughter] went in and lay with her father, and he had no knowledge of her lying down, or her getting up. [34] And it came to pass on the morrow (ממחרת), that the first-born said to the younger, 'See, last night (אמש) I lay with my father. Let us make him drink wine tonight also, and you go in and lie with him, so that we may keep alive our father's seed.'"

By applying Ibn Ezra's logic here, we would derive the following meaning of the above verses: the first born daughter lay with her father at night, but the next morning the daughters spoke nothing of the incident; only on the following morning did the first-born daughter finally say to her younger sister, "Let us make him drink wine tonight also, etc." The language of verse 34 also confirms the unlikeliness of Ibn Ezra's line of thought. Verse 34 explains the relationship in time from the point after the event occurred looking backwards: "See, last night (emesh) I lay with my father." The Hebrew word emesh can only mean "last night", and cannot possibly mean "two nights ago", the closest Hebrew word for which would be "shilshom"18

Therefore, it is clear that the Ibn Ezra's explanation is a contrived explanation with the singular goal of defending the traditional Rabbinical understanding of the date of the Omer HaTenufah offering. It is not an intellectually honest and objective exposition of the facts at hand.

The Book of Joshua 5:11 brings strong anecdotal evidence in favor of the Karaite view by showing that the ancient Israelites under the prophet Yehoshua bin Nun seemed to interpret the Torah in a way that is inconsistent with the Rabbinical interpretation. One Rabbinical commentator, Ibn Ezra, practically trips over himself in a pathetic attempt to retrofit this verse to the Rabbinical understanding of the Omer HaTenufah offering. In doing so, he comes off as a poor apologist for Rabbinical Judaism.

__________________________________________

I hope that this study has proven to be a valuable one. Moreover, I hope that you will see it as a fair consideration of the evidence at hand and that, as such, it may serve as a positive example of Karaism and of the Karaite methods of interpretation. To some people it won’t matter. Some people will never give up their Rabbinical Judaism, just as so many ancient Israelites refused to give up their Ba’al worship. In fact, Rabbinical Judaism is, in many ways, nothing less than modern day Ba'al worship, in which the stone idols of old are replaced with human idols, both dead and alive, known as "The Sages", "Rebbe" and "Gadol HaDor".

Thus, Rabbinical Judaism, despite what it claims, abrogates responsibility to Elohim, and places man in Elohim's place: man can create with the Torah, weave stories and new ideas from it, interpret it freely and, under the guise of following Elohim, can send Elohim out into the desert like the goat to Azazel.19

Man can mention Elohim’s name with his mouth and at the same time not follow Elohim’s ways in deed, as the prophet Isaiah so adeptly observed:

"... This people approaches me with its mouth, and with its lips it honors me, but its heart is far from me, and their fear of me is merely a commandment learned by rote from men." [Isaiah 29:13].

On the other hand, what is Karaism? I will conclude with the poem "Who is a Karaite" that I recently wrote, to explain what Karaism is in my eyes.

__________________________________________

The Tanach surges through his veins as if it were his own blood.

He strives to live his life according only to the code of the Torah.

He accpets no other systems of law or culture as substitute.

Ancient Hebrew, the language of the Tanach, drips from his lips.

He has a clear vision for the re-establishment of the ancient and eternal culture of

the People of Israel in the Land of Israel.

He is an independent thinker who is not afraid to walk the lonely path of truth.

He is close to nature and lives among the plants and the animals.

He is kind to man, animal, plant and the earth.

Because of this he is loved by all good men, Israelite and non-Israelite alike.

He sings, dances and plays musical instruments to Elohim.

He cries out to Elohim when in pain.

He respects other men, but bows to no man, only to Yehowah alone.

All praise to Yehowah, Creator of Heaven and Earth!

May Yehowah Be With You,

Melech ben Ya'aqov,

Jerusalem, Israel

2See Isaiah 51:22.

3Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Menachot 65a; though the passage mentions the Boethusians, they were a Jewish sect closely related to, if not a development of, the Sadducees.

4All translations in this article are the author's, unless stated otherwise.

5Leviticus 23:6

6Therefore, if the 14th of the First Month falls on the Shabbath, this will be the Shabbath spoken about in Leviticus 23:11 and 15, according to the traditional Karaite interpretation. However, this is not explicit in the Torah. In fact, the Torah is quite silent about when this special Shabbath falls, hence the interpretation of the Rabbis which says that it is not the Shabbath at all but rather the first day of Hag HaShavuoth. Jerusalem-based archaeologist Tzahi Zweig takes a different approach, based on Deuteronomy 16:9: "... From the time the sickle is first upon the upright grain stalks, you shall begin to count seven weeks." Each year, he contacts barley farmers in the land of Israel to determine when the barley harvest will begin. He then declares the following Shabbath to be the one spoken about in Leviticus 23:15,16.

7For more information about the fixed Rabbinical calendar and its similarities to and differences from the observation-based Biblical calendar, see Karaite Insights' three-part lecture series which can be found at: https://karaiteinsights.com/php/video.php5.

8This can be borne out through a thorough examination of the verses which use the word shabbath. While a sample of such verses follows, I encourage the reader to look at others, so that he might get his own sense of the meaning of the word.

9The reference is usually in the form "Shabbath shabbathon".

10Note that the word "melakha" is short and terse, while the phrase "malekhet avoda" is longer and more rambling. Thus, in Leviticus 23, the Torah uses onomatopoeia to express the greater strictness of the former and the greater leniency of the latter. Rich usage of the ancient Hebrew language, including metaphor, allegory, word play, etc. is part and parcel of the language of the Tanach.

11Another, mathematical, way of stating the principle of Occam's Razor is that the correct explanation of a phenomenon is the "minimal set" encompassing all the relevant data.

12If someone can point me to a Rabbinical commentary which does make this point, I would be grateful.

13The fact that the word totafoth seems to be in the plural according to the rules of Hebrew grammar for feminine nouns does not mean that it cannot be "a remembrance", i.e. in the singular. Many scholars have posited the idea that totafoth is not a Hebrew word at all, but a foreign loan word, perhaps from the Egyptian. Note, by the way, that Exodus 13:9 is referring to the eating of matzah while verse Exodus 13:16 is referring to the redemption of the first born.

14I often like to refer to Moshe ben Amram as "Moshe Karaieinu", as a polemical response to the Rabbis' calling him "Moshe Rabbeinu". We should never allow the Rabbis to retroactively co-opt Moshe for their movement since Karaism is almost certainly closer to the way he understood the Torah.

15As mentioned in an earlier footnote, the Torah is extremely fond of and adept at employing word plays, and examples abound; for instance, see Genesis 2:25 – 3:1.

16Based on the evidence in these verses, we can posit that in this first year of the Israelites' entrance into the Land, the structure of the calendar was as follows: the day of the Passover sacrifice was the Shabbath ("Saturday") and therefore the Omer HaTenufah offering was brought the following day, Sunday, which was the 15th of the First Month.

17"And they traveled from Raamses in the First Month on the 15th day of the First Month, on the day after the Passover (ממחרת הפסח), the Children of Israel exited with the upper hand before all the eyes of Egypt." [Numbers 33:3]

18Applying the Ibn Ezra’s logic to other verses yields equally illogical results. For instance, consider the following verse:

Numbers 11:32: "And the people got up and gathered the quails all that day, and all night, and all the next day (וכל יום המחרת). He that gathered the least gathered ten heaps. And they spread them out all around the camp."

Applying the Ibn Ezra’s logic, the Israelites would have gathered quails all day and all night, but the following day they would have done nothing. Instead, they would have rested from gathering, and only on the day following this day of rest would they have resumed their gathering.

As if all of this were not enough proof, Numbers 33:3 tells us explicitly what is meant by the phrase "the morrow after the Passover", and it is not what the Ibn Ezra claims:

Numbers 33:3: "And they journeyed from Raamses in the First Month, on the 15th day of the First Month; on the morrow after the Passover the children of Israel went out with a high hand in the sight of all of Egypt."

Here, the Torah states clearly that the "morrow after the Passover" is the 15th of the First Month, not the 16th of the First Month as the Ibn Ezra would like to claim! The Ibn Ezra’s response to this: here the Passover referred to is "Israel’s Passover" and not "God’s Passover". Talk about picking and choosing! Note that he says this even though the Torah uses the exact same words as in Joshua 5:11.

19Leviticus 16:8

This Article Has 1 Comments

Home

Home